Scientists have long wondered what the evolutionary purpose of menopause is. Why would limiting the time a female individual has to procreate have advantages for the six known species that experience this hormonal change?

Well, we may be closer to learning the answer to that, thanks to a study just published in the journal Current Biology. The study shows that older female killer whales direct their post-menopausal energy toward lowering the socially-inflicted injuries their sons receive.

The study comes from researchers out of the University of Exeter, the University of York and the Center for Whale Research in Washington state. They studied 6,934 images of injuries on resident killer whales that live off the Pacific coast of North America. They combined the images with demographic data from five decades of studying 103 whales, and looked at resource abundance data to make their conclusions.

The researchers used rake marks along the orca’s bodies to quantify injuries, which is possible because their preferred prey, fish, cannot inflict such scars. As an apex predator in their ecosystem, no animal could inflict those kinds of wounds except other orcas.

MORE: Gray whales come to tour boat’s captain for help with parasites

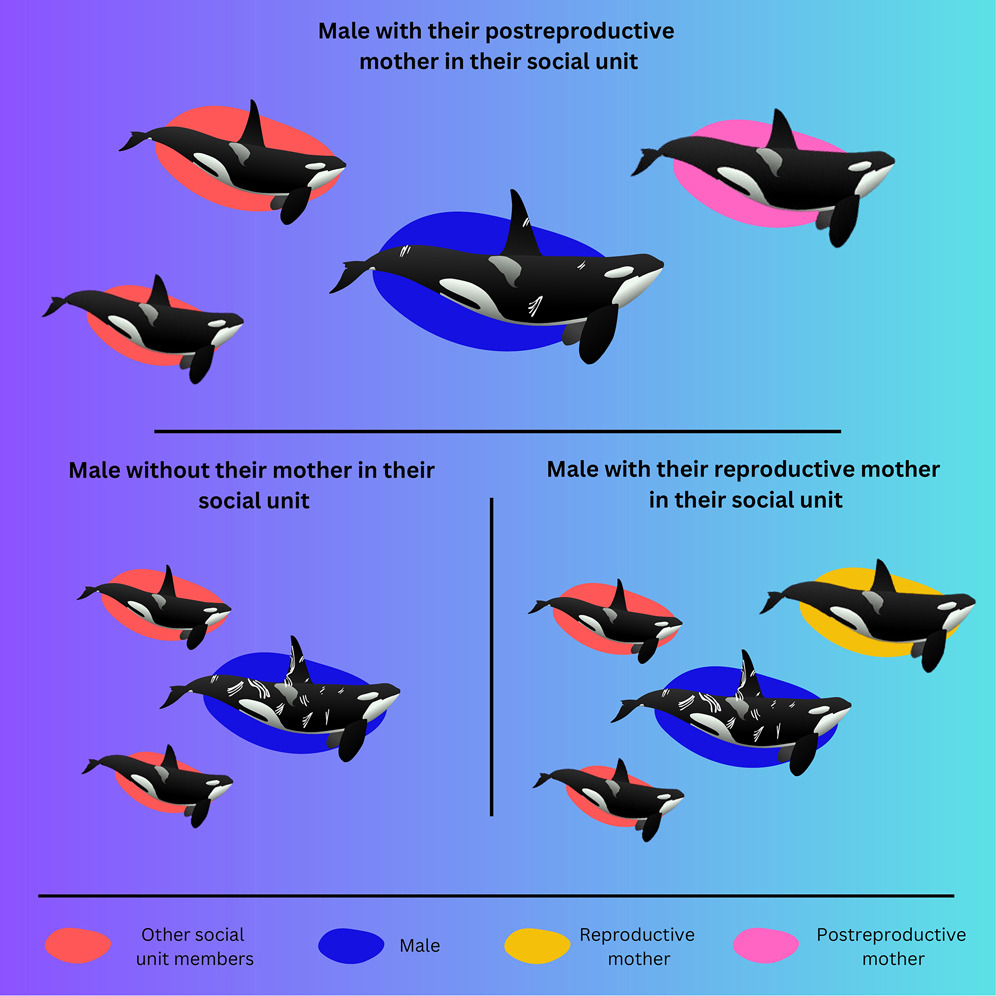

They discovered that in orca populations where mothers and sons were traveling together, the males experienced fewer injuries. This is compared to killer whale males without their mother in the same social unit and killer whale males whose mother was in their social unit, but was still of reproductive age.

Interestingly, the study found that this did not happen with killer whale moms and their daughters, or with grandmother whales with their offspring, whether male or female. The results also didn’t find that post-menopausal female orcas provided any similar benefits to the group in general.

“It was striking to see how directed the social support was,” said co-author Darren Croft, an animal-behavior scientist at the University of Exeter, in a press release. “If you have a post-reproductive mother who’s not your mother within the social group, there’s no benefit. It’s not that these females are performing a general policing role. These post-reproductive mothers are targeting the support they are giving to their sons.”

Previous research has shown that male killer whales have a strong bond with their mothers, sometimes staying close to them throughout their lives. One study in 2012 noted that mother killer whales increase their son’s chances of survival by eight times if the male is over 30. Another recent study done on the southern resident whale population even indicated that killer whale moms will forego having additional offspring to look after their weaned, fully mature sons.

It’s unclear at this point exactly how post-menopausal whale moms are providing this social support.

“It might be that they use their enhanced knowledge of other social groups to help their sons navigate risky interactions. They might be signaling to their sons to avoid the conflict,” primary author Charli Grimes of the University of Exeter told The Guardian. “Or it might be that they involve themselves in a conflict directly.”

Whatever the mechanism, this research agrees with the current information on menopause, which is that menopause allows females of different species to provide other nurturing social benefits — like teaching, caregiving, and food-sharing — to members of their families and communities.

This story originally appeared on Simplemost. Check out Simplemost for additional stories.