Black holes contain mysteries that we can’t begin to fathom just yet. This was proved recently when astronomers discovered that black holes remain active long after swallowing a star.

To understand why this is such a big deal, you first have to understand what scientists originally thought happened inside a black hole. First discovered by astronomers in 1964 after having been theorized about since the 18th century, black holes are not actually holes. They are areas in space, often remnants of large stars that have ended their lives in supernovas, in which gravity is so heavy that no light can escape.

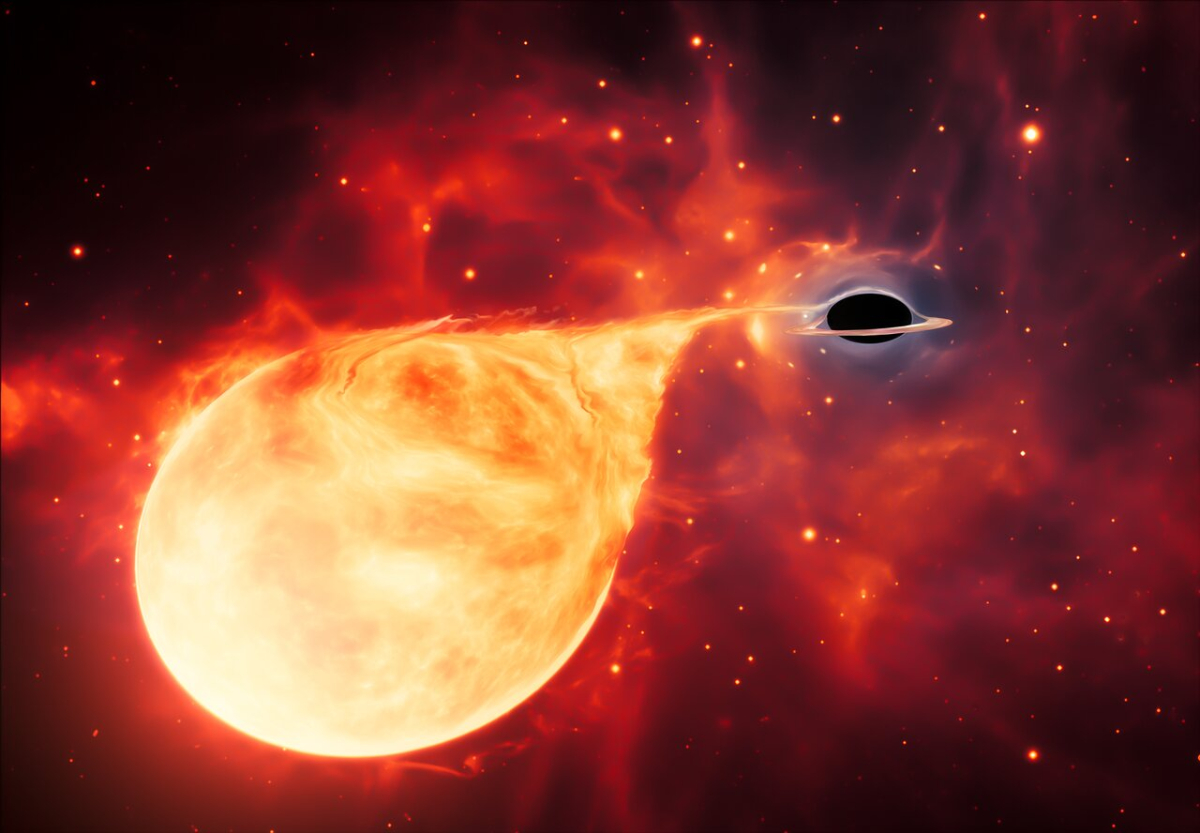

When a star comes close to a black hole, it gets sucked in and experiences “spaghettification,” as Stephen Hawking famously termed it in his “A Brief History of Time.” This refers to how gravitational pull affects different parts of an object as it goes into the black hole.

When a star is destroyed in this manner by a black hole, it causes a tidal disruption event, commonly referred to as a TDE. A TDE causes an eruption of material from the object being pulled in. Part of the material forms around the black hole and creates an “accretion disc,'” while the other part of the star shoots off in visible rays of light and energy that can be picked up by astronomers on Earth.

Scientists used to believe that TDEs would occur within a matter of months after a star encountered its death in a supermassive black hole.

But now, a shocking finding made by scientists at the Harvard and Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics suggests otherwise. In 2022, radio astronomer Yvette Cendes and her team discovered a black hole that showed activity three years after swallowing a star.

“This caught us completely by surpriseâ — âno one has ever seen anything like this before,” Cendes, a research associate at the center and lead author of the study, said in a statement. “It’s as if this black hole has started abruptly burping out a bunch of material from the star it ate years ago.”

After this shocking finding, the researchers at the Center for Astrophysics began studying 24 previously active black holes to see if they could find renewed activity at these sites as well.

And they did: They discovered that over half of these black holes “woke up” again years after swallowing a star, with one black hole even “burping” up star matter six years later. On a thread she posted to X (formerly Twitter), Cendes explains the findings and provides a chart tracking how the black holes re-brightened months or years later.

The orange-brown line, furthest to the right, shows a star that “turned on” again six years after disruption.

For those who want plots, here is a simplified version of Fig1 in the paper. AT2018hyz+ ASASSN-15oi are previously known, AT2019dsg+ iPTF16fnl are the ones we saw rebrighten. And there is a LOT going on! (Upside-down triangles are non-detections, colored symbol is a detection.) pic.twitter.com/fMJbp3Fnu8

— Yvette Cendes (@whereisyvette) August 29, 2023

MORE: NASA scientists discover Mars is spinning faster

In the thread, Cendes explains that this finding means that everything scientists thought they knew about TDEs and accretion discs could be wrong. While she rules out ideas about potential time warps (as she says black holes exist way too far out in space for Earth years to have a measurable effect), she says it could be that accretion discs actually don’t form shortly after a star’s death.

“What if, for example, the optical flash we see is not from an accretion disc forming, and instead is from streams of material hitting each other as the star is unbound, and then the disc itself takes years to form?” Cendes wrote on Reddit. “How, we aren’t quite clear, but this is insanely exciting as it points to an entirely new laboratory for physics!”

But the excitement here is it gives us *a new laboratory to test physics*! We can't build a SMBH on Earth, so to study the extreme gravitation around them requires observations like these. We have a brand-new parameter space to explore, and I can't wait to see what we discover!

— Yvette Cendes (@whereisyvette) August 29, 2023

The astronomer explains that we don’t yet know the full ramifications of these findings but that it has created a “paradigm shift” in what scientists thought they knew about black holes.

MORE: India’s Chandrayaan-3 spacecraft shares photos from moon’s south pole

You can read the preprint paper from Cendes and her team here on arXiv.

This story originally appeared on Simplemost. Check out Simplemost for additional stories.